Why do I write?

That was February’s topic over at YA Outside the Lines, where I blog monthly with a group of amazing authors. The topic came at an opportune time for me. I turned in my fourth YA novel to my editor in early December and since then I’ve been asking myself that question. A lot. Along with two additional big questions:

What do I want to write next?

Do I have something meaningful to say?

I don’t have answers to the latter questions, not yet. My post-draft funk is lasting longer than usual this time. As much as I look forward to completing a novel, I dread the quiet that happens after, when one set of characters stops talking to me and the conversation with the next set has yet to begin. So I’m grateful that this blog post is forcing me to both answer the question at hand and do some actual writing.

For a long time, whenever someone asked me I why I write, I’d say “To make people laugh.” Growing up, Erma Bombeck and Judy Blume were my heroes. For years, I made it my goal to be like one or both of them in my approach to writing. My journal entry about Tammy the talking toothbrush was a huge hit in fifth grade. In high school, I killed with my mini play about Dante’s Inferno and the accompanying slideshow depicting Dante’s vacation in hell with the poet Virgil. Midway through my freshman year in college, the personal narrative I wrote called Plight of the Poncho made the other kids in the class notice I was alive. (Always a good thing.) It was a tale of woe involving a hand-crocheted red and white poncho, a giant sliding board, and an impatient pack of first graders during recess. My writing instructor later confided that she laughed out loud while grading my essay and wound up reading the funny parts to her husband. “You’ve got talent,” she said.

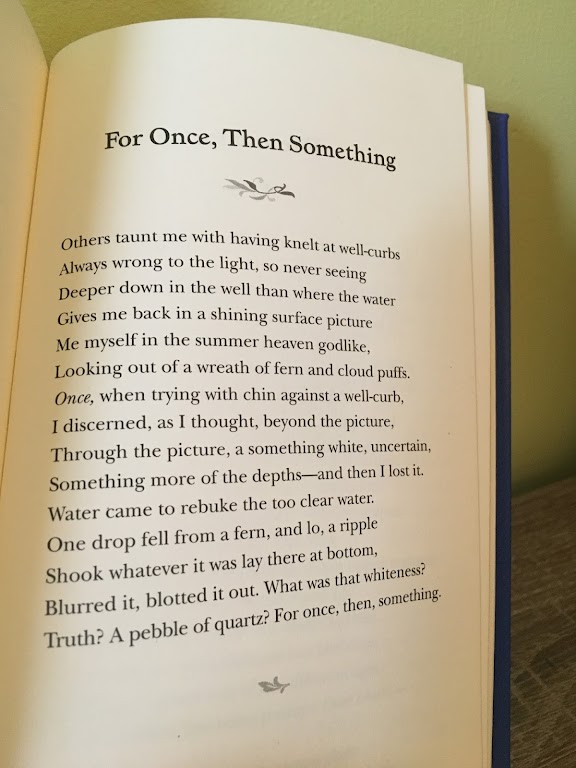

It was definitely “a moment” on my journey. A moment that made me want to write, but not one that made me fully understand why I write. My brief stint in grad school brought me one step closer to understanding the hows and whys of self-expression. We were reading Robert Frost’s For Once, Then Something, a poem I’d read often on my own because S.E. Hinton made me want to read all the poems in my Robert Frost anthology. But until my early twenties, I never quite understood it. The poem begins:

Others taunt me with having knelt at well-curbs

Always wrong to the light, so never seeing

Deeper down the well than where the water

Gives me back in a shining surface picture

Me myself in the summer heaven godlike

My heart beat faster as my professor read it, and not because he was trying to turn Frost into soft porn like he did with just about every other poem we read that semester. But because I got it! I finally got it! The meaning hit me so hard I snapped my head up and I looked around the class to see if everyone was having the same visceral reaction.

Frost wasn’t merely referencing Narcissus, or writing about some guy who got mocked for spending too much time looking down a well. This was a poem about artists and the often painful, messy process that goes into creating meaningful art. You have to crane your neck down dark wells, crawl down rabbit holes, and prowl around in The Upside Down. (Yes, I love Stranger Things. Best thing I’ve seen in a long time.)

Once you’ve visited the dark places of your soul, then all you have to do is share what you’ve found with the entire world in a way that engages and entertains the audience you’re trying to reach. Sure. No problem.

“I don’t wish on any of you the kind of life that makes people great poets,” my professor said that semester. I wish I could remember his name because I never forgot those words.

Or the story he told us about the poet Robert Lowell. In his 1973 book, The Dolphin, Lowell borrowed extensively from letters written by his ex-wife, whom he’d just divorced after 23 years. Lowell’s friend and confident, poet Elizabeth Bishop, thought maybe Lowell had gone too far down the well and overshared “…art just isn’t worth that much,” she wrote to him.

I get where she was coming from, Lowell had perhaps crossed a line, or a canyon, in sharing something so private. But on the other hand, I admire artists who do the hefty lifting for us, digging more deeply, feeling more intensely, and exposing themselves to more pain and criticism so that we don’t have to. We benefit from their willingness to explore connections between the messier parts of human existence and the whole damn universe in the hopes of finding, like Frost’s narrator, “a something white, uncertain.”

I know I haven’t spent nearly enough time kneeling at well-curbs, but I’m so very thankful for and inspired by people who do. With each new project I try to push myself farther. To discover my own truths, my own something whites, and share what I’ve learned through my stories.

That’s why I write.

But I still hope I make people laugh.

“When I stand before God at the end of my life, I would hope that I would not have a single bit of talent left and could say, I used everything you gave me.” Erma Bombeck